Four Great Grandfathers intertwines the lives of four remarkable men, each facing the tumultuous events of the early 20th century in their unique ways. Together, these stories paint a vivid picture of courage, sacrifice, and the complex tapestry of identity during a period of profound historical significance.

John Williams: A Dublin Fusilier’s Sacrifice in the Great War

BIRTH 18 MAY 1884 Dublin, Ireland

DEATH 25 APR 1915 St Julian, France

DUBLIN (COI) , Parish/Church/Congregation – MOLYNEUX CHAPEL Baptism of JOHN WILLIAMS of 6 BRIDE ST on 1 June 1884 Father ROBERT WILLIAMS Engine Fitter Mother FANNY WHITAKER Group Registration ID 10438664

John Williams’ life was shaped by the turbulent events of his time. Born on May 18, 1884, in Dublin, he was a British Irishman of Welsh and English descent, living in a city on the cusp of Irish independence. As a member of the Church of Ireland, he reflected the diverse religious landscape amid rising political tensions.

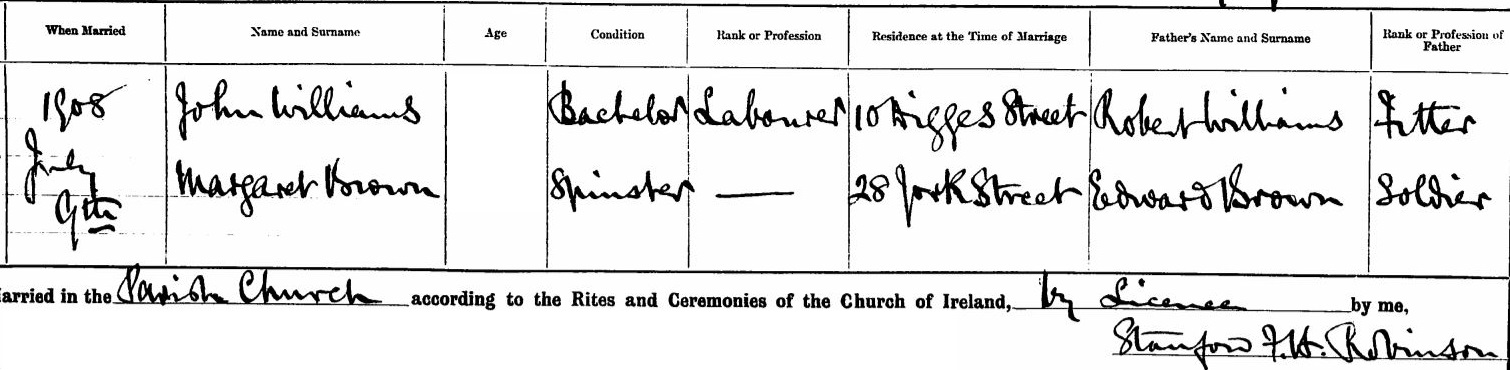

In his youth, John worked as a messenger and married Margaret Brown in 1908; her father had served as a professional soldier in India with the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, the regiment John would soon join. This connection may have influenced his decision to enlist. Their daughter, Mary Margaret, was born in 1913, just before the Great War began.

When war broke out, John enlisted in the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers. On August 7, 1914, he departed Dublin with the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and was sent directly to France, where he engaged in the first battle at Le Cateau on August 26. This battle delayed the German advance toward Paris, causing significant casualties and leading the Germans to underestimate British forces.

Despite not initially receiving a retreat order, the Dublin Fusiliers contested the German advance, allowing the British left wing to retreat with minimal interference. The battalion later fought in the Battle of the Marne, where the Allies halted German progression just 48 km from Paris, marking the transition to trench warfare. Edward Spears, a British officer, later reflected on the unawareness of the soldiers facing the battles ahead:

“I am deeply thankful that none of those who gazed across the Aisne of September 14 had the faintest glimmer of what was awaiting them.”

By autumn 1914, the 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers had dwindled from 1,045 men to just 488, with John among the survivors. He likely took part in the famous Christmas Truce of 1914, where soldiers from both sides converged in No Man’s Land—this fleeting moment stood in stark contrast to the futility of war that followed.

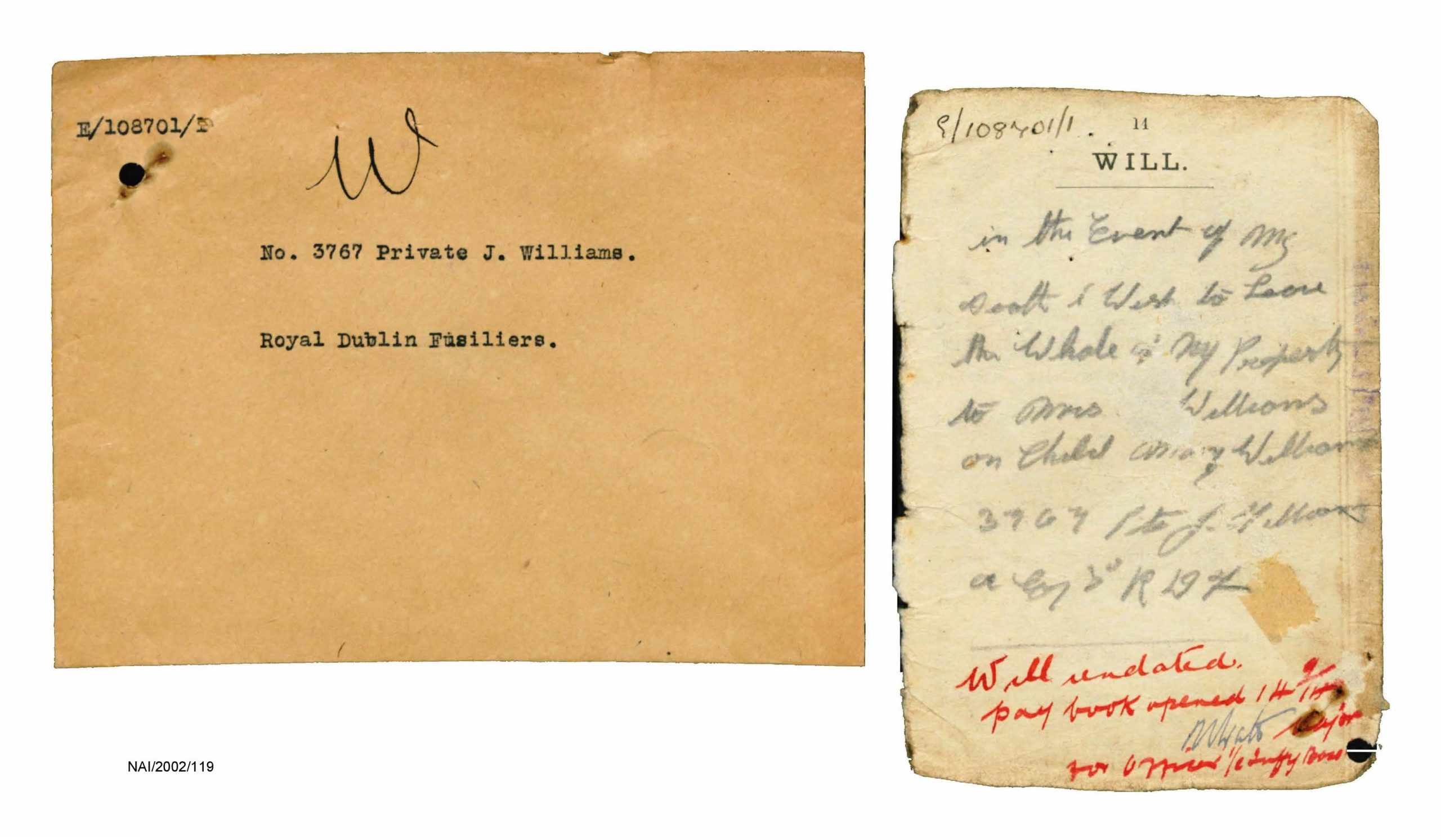

On April 24, 1915, John was in Belgium for the Battle of St. Julien during the Second Battle of Ypres, where his battalion faced severe casualties from a German bombardment and poison gas attack. Of 666 soldiers, only one officer and 20 others survived by nightfall. John initially survived but died the following day during a devastating attack that cost thousands of lives. He left a will in a trench, bequeathing his belongings to his wife and daughter.

John Williams was 30 when he died on April 25, 1915. His name is permanently honoured on the Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial in Belgium, commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

A few years later, his wife Margaret remarried an Irish Catholic and moved to Scotland with John’s young daughter, Mary Margaret. In a twist of fate, Mary Margaret would later marry one of the sons of Robert Connolly, another brave soul who served in the Great War.

Robert Connolly: A Legacy of Bravery and Resilience in the Great War

BIRTH 20 AUG 1883 • Drumdallagh, Loughguile, Antrim, Northern Ireland

DEATH 19 FEB 1941 • 111 West Princes Street, Glasgow

Reg Number u/1882/30/1005/7/75 District Ballmoney (pre-1973 Q4) Sub district Dervock Robert James Connolly 20th August 1883 Mother Catherine Campbell Father James Connolly (Sub Post Master)

Robert Connolly’s life was marked by courage, resilience, and sacrifice. Born on August 20, 1883, in Drumdallagh, Antrim, Robert grew up amid the early troubles of the region. His family, of Scottish settler and ancient Irish descent, converted to Protestantism to retain their land, a decision reflecting the complex socio-political landscape of the time. His mother, Catherine Campbell, a staunch supporter of the Ulster Covenant, signed a petition by ‘The Women of Ulster’ demanding that Northern Ireland remain part of Britain.

In 1905, seeking adventure and perhaps an escape from local tensions, Robert emigrated to the United States, where he spent a few years driving trains in Philadelphia. Tragedy struck when his American wife, Susan Kelly, died from influenza three years after their marriage in New Jersey.

Despite this loss, Robert remained in America for a few more years, working as a train driver for the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) across the Midwest, until the outbreak of the Great War compelled him to return to Britain.

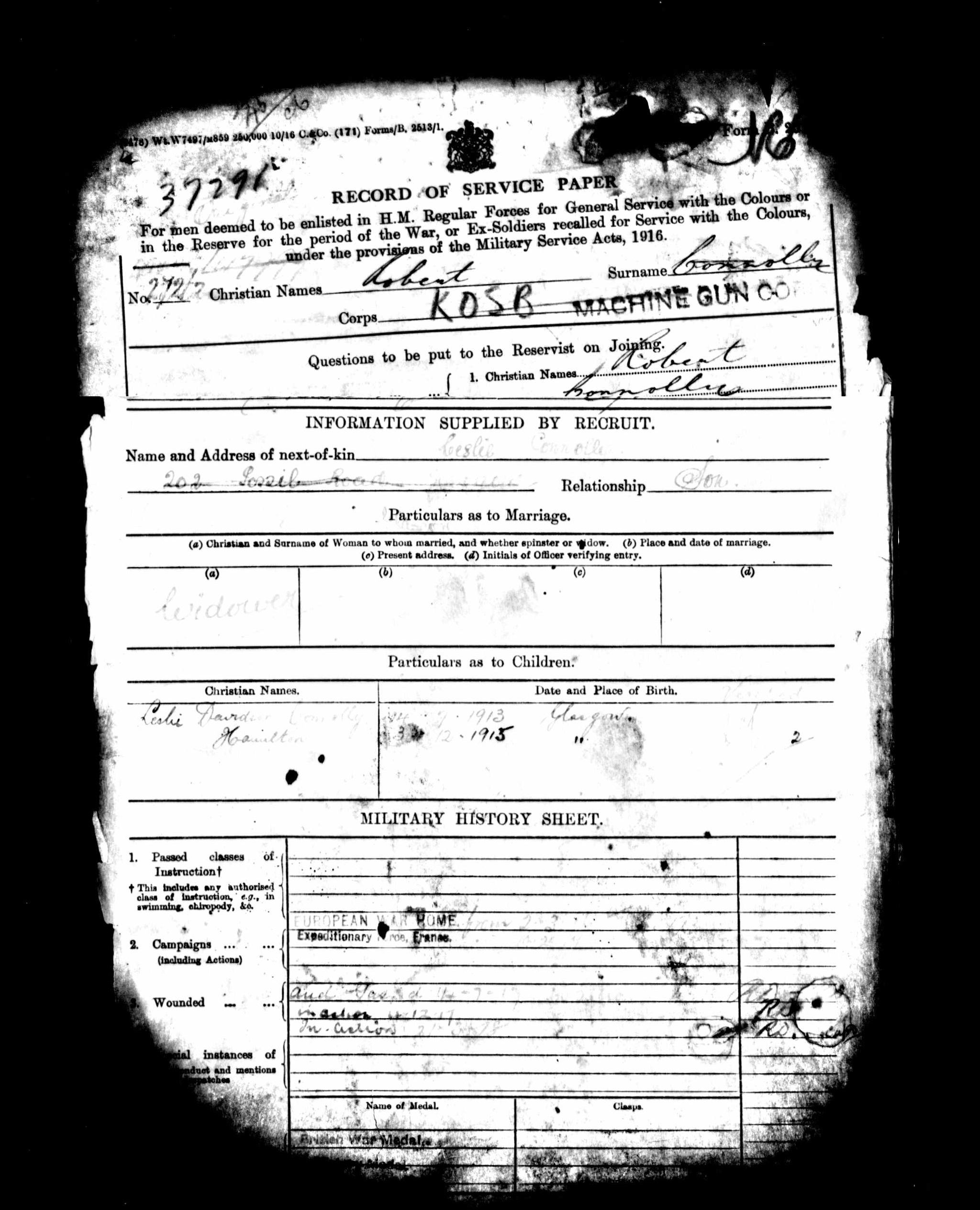

Settling in Scotland, Robert enlisted in the British Army in 1915. He arrived in Boulogne-sur-Mer near Calais in northern France on March 2, 1916, as a private in the King’s Own Scottish Borderers. Soon after, he was recruited for training with the newly formed Machine Gun Corps, an elite unit known for its perilous role on the front lines. This corps, often referred to as the ‘suicide squad,’ gained a reputation for bravery, as its members were typically the first into battle and the last to leave. Robert bore a tattoo of the skull and crossbones, the emblem of the 100th Machine Gun Corps, on his arm. His experiences in Northern Ireland and the Wild West likely contributed to his swift selection for this elite corps upon his arrival in France.

Throughout his service, Robert’s record reflects bravery and endurance. In July 1917, he sustained his first injury when he was gassed at the Hindenburg Line in Flanders, a common but dangerous risk of trench warfare. Despite this setback, he continued to serve with distinction, embodying the spirit of the corps. Later that year, in September, he fought at Polygon Wood during the Battle of Passchendaele, using Lewis guns to help drive back the enemy. In December 1917, he was wounded again, though the details of this injury remain unclear due to damage to his records from a Nazi aerial attack on the British War Records office during the Blitz.

In 1918, Robert’s courage was tested further on March 21, when he and his 100th Machine Gun Company faced the onslaught of Germany’s elite shock troops during the Spring Offensive. The Machine Gun Corps was among the first to engage the enemy, battling hand to hand against some of Germany’s most hardened troops. Robert’s strength and determination were crucial in holding the line during this critical period, but he emerged with a half-inch scar on his cheek, which permanently affected his teeth and vocal cords.

After the war, his War Office records indicate he was a widower who settled down with his second wife, Christina Gow, with whom he had two sons. While Christina was with him until the end (1941), and Robert’s name appeared on her death certificate many years later(1972), his death record still listed Susan Kelly (1909) as his wife.

Shadows of the Great War: The Legacy of William Yardley

BIRTH 19MAY1884 • Vennel Street, Dalry, Ayrshire

DEATH 26 DEC 1925 • Lightburn Hospital, Shettleston, Lanarkshire, Scotland

YARDLY WILLIAM M 1884 587/ 149 Dalry (Ayr)

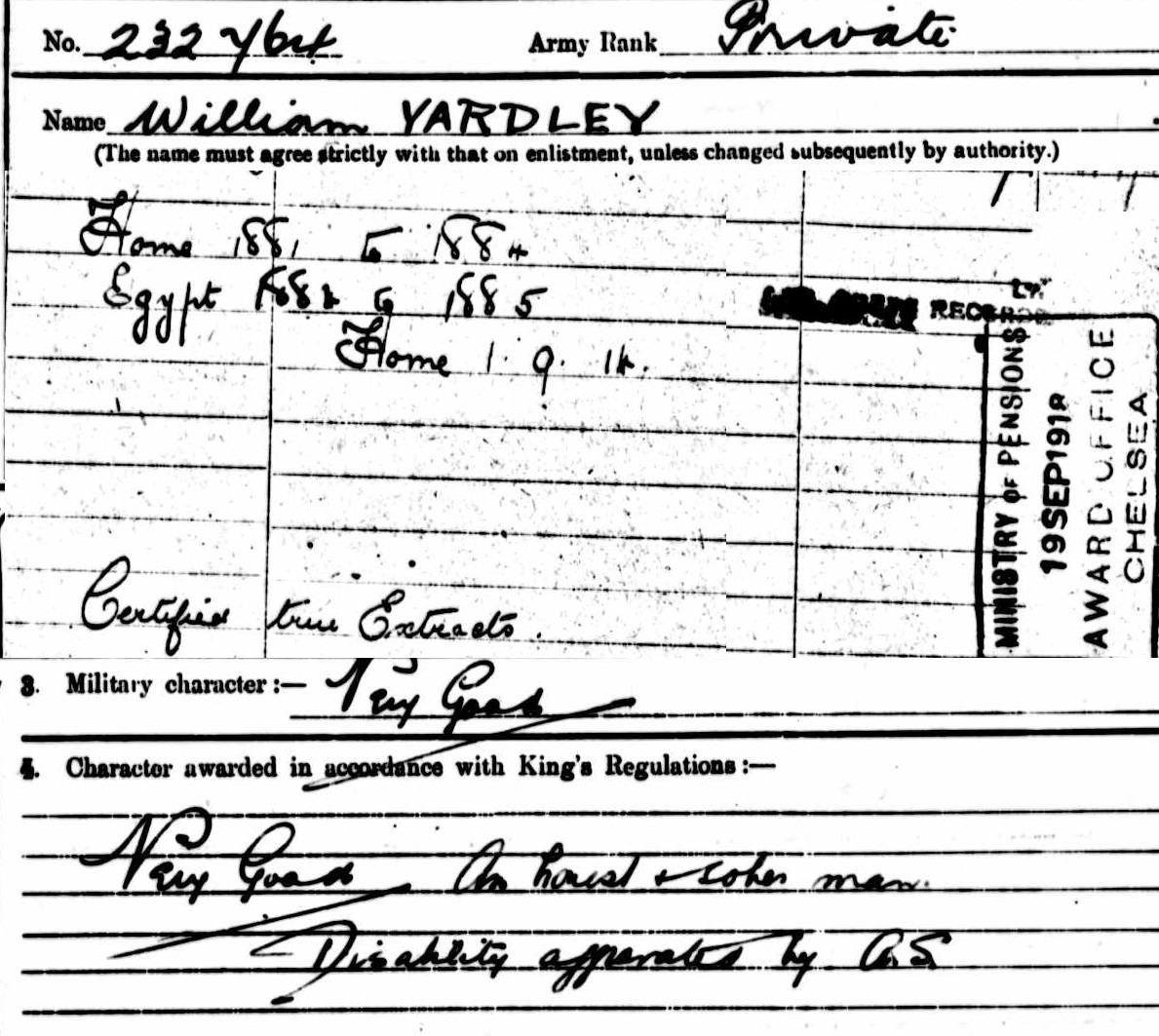

William Yardley was born on a brisk spring morning on May 19, 1884, in the mining town of Dalry, in the Garnock Valley of Ayrshire. The rolling green hills and industrial towns of North Ayrshire shaped William’s early life, along with his family’s generations of mining and military service. Following in his father’s footsteps, William enlisted in the Royal Scots, inspired by his father, William Yardley Senior, who had fought in the Anglo-Egyptian War (1882-85) and was discharged in 1919 at the age of 60.

Within a year of the Great War’s outbreak, one in every four Scottish coalminers had enlisted, with many more eager to join. The government eventually had to ban pitmen from active service to ensure that the mines remained fully manned. However, William’s journey into darkness had already begun.

He arrived at Boulogne on the S.S. Invicta on May 11, 1915. His introduction to the brutal reality of trench warfare came just nine days later, on May 20, when the 11th Royal Scots, under temporary command of the 6th Division, entered the front line near Armentières. Here, the Germans bombarded the British lines for two days following William’s arrival.

A month later, the Anglo-French Conference in Boulogne revealed growing tensions between the allies. The French pushed for a large-scale assault while the British, still nurturing and training their New Army, hesitated, fearing they would not be ready for a major offensive until 1916. The French, having more troops at the time, won the argument, thrusting William and his comrades into battle before they were fully prepared.

Loos, Britain’s largest offensive of 1915, became William’s crucible. On September 25, the 11th Royal Scots launched a major assault on the German line, only to face fierce resistance and heavy casualties. The British use of chlorine gas became disastrous when the wind shifted, blowing toxic clouds back onto their troops. Amid the chaos, William miraculously emerged unscathed.

The summer of 1916 marked a new chapter as the British Army, now a formidable force of 1.5 million men, sought redemption for past failures.The Battle of the Somme was intended as this reckoning, featuring an intense artillery barrage aimed at obliterating German defenses. However, the Germans, anticipating the attack, had fortified themselves in concrete-reinforced tunnels, rendering the bombardment largely ineffective. The British soldiers, including William’s 11th Battalion, were ordered ‘Over the Top’ into a veritable slaughterhouse. The first day alone saw over 19,000 British soldiers fall, almost half of them Scots.

William’s battalion was also involved in the attempt to liberate the village of Longueval. Despite their valiant efforts, the village remained a German stronghold until their relief on July 17. The Somme would later be remembered as the graveyard of Scotland’s local battalions, with British losses mounting to 400,000 by November.

A turning point came with the Battle of Vimy Ridge in 1917, where Canadian forces, using innovative tactics such as the creeping barrage, achieved a stunning victory. William’s granddaughter, Ann Marie, would later marry the grandson of Robert Connolly, an elite fighter in the Machine Gun Corps, whose heroics during this battle saved William’s beleaguered Royal Scots and enabled the British Army to advance.

However, fate dealt another blow during the German Spring Offensive of 1918, when a shell explosion left William with a severe wound, ending his active service. He was honourably discharged and returned home on March 27, 1918, resuming his role as a miner. Although lacking formal authority, he was respected by his peers for his expertise in identifying and extracting ores.

Tragically, the scars of war lingered and a few years later contributed to his untimely death from pneumonia during a flu outbreak. On December 26, 1925, Boxing Day, William Yardley passed away in Shettleston, Lanarkshire, at just 41. His daughter Mary, Ann Marie’s mother, was only five years old at the time.

Catherine, his widow, had her own poignant story. Born on July 28, 1894, she married William in Cambuslang, Lanarkshire, shortly before the Great War broke out on her 20th birthday. Her brother John, two years her senior, perished in France just a month before Armistice Day. Serving in the 15th Scottish Division, he encountered the US 1st Division while trying to liberate the French town of Buzancy. The inexperienced Americans suffered greatly, leaving a tragic toll in the cornfields. Under cover of darkness, the Scots cleared the fallen and joined the remnants of the 1st Division alongside a French flamethrower unit. Together, they launched a daring assault through the streets of Buzancy, exemplifying courage and brotherhood. Their efforts were so impactful that a French commander ordered a memorial to be built for the last fallen Scottish soldier—the only French tribute to a British regiment during the war. Tragically, John’s heroism was cut short when the Germans, enraged by their defeat, unleashed a bombardment that claimed his life.

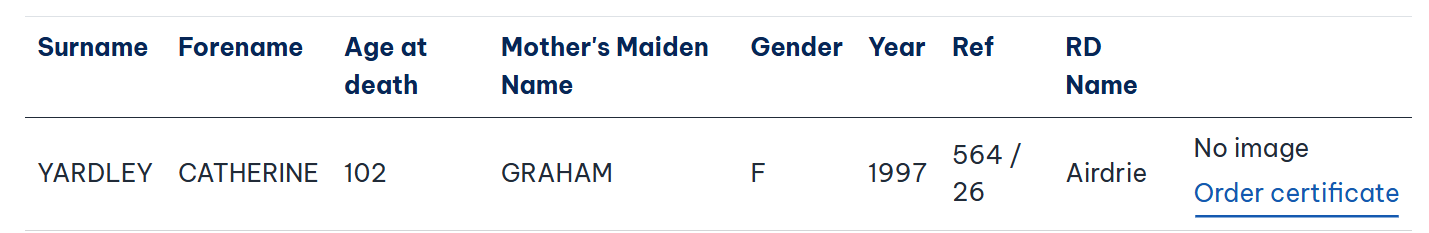

Catherine lived until 1997, dying shortly before her 103rd birthday. She stood as a pillar of strength for her family through an era marked by the deep scars of two world wars. The legacy of the Great War lives on, not merely in the pages of history books, but in the narratives of individuals like William Yardley and Catherine, who endured the trials of two global conflicts and a society forever changed by a generation of shattered families and men.

From Irish Roots to a Scottish Soul: The Untold Story of Francis Mohan

BIRTH 16 FEB 1878 • Dunkineely, Donegal, Ireland

DEATH 5 DEC 1956 • Blantyre, Lanarkshire, Scotland

PARENTS: Bernard Mohan and Grace Tummoney National Library of Ireland; Dublin, Ireland; Microfilm Number: Microfilm 04599 / 01

Francis Mohan was born on February 16, 1878, in the small village of Dunkineely, approximately 11 miles (18 km) from Donegal in northwest Ireland. Nestled between coastline and mountains, his family had been small-scale subsistence farmers in the area for at least two generations. The surname Mohan is an anglicised version of the ancient Gaelic O’Mochain, derived from a diminutive of “moch,” meaning ‘early’ or ‘early one,’ possibly linked to a chief in the region from ancient times.

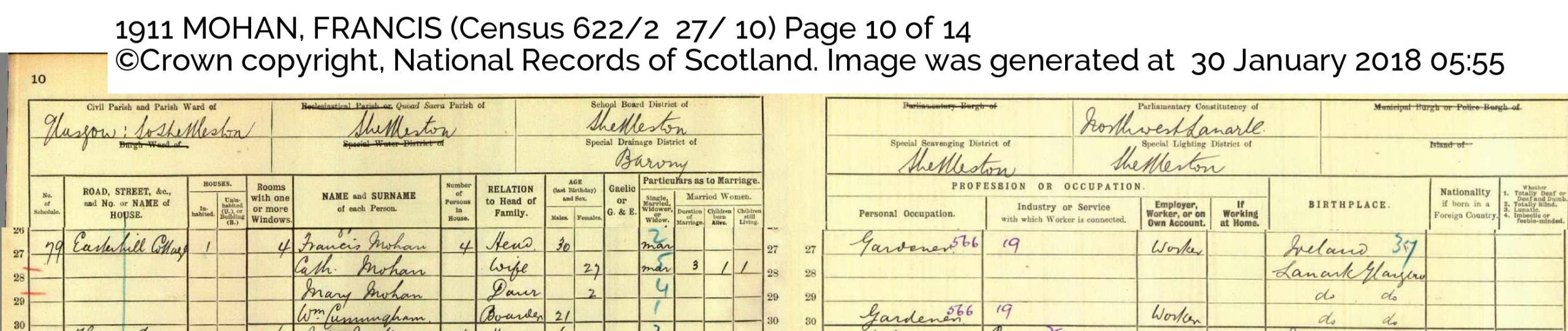

Many of Francis’ siblings emigrated to Philadelphia, but according to local accounts, Frank boarded the first boat available when the British Army and the infamous B-Specials began rounding up young men; this boat happened to be headed for Glasgow around 1900. Though he settled in Scotland, Francis frequently returned to Donegal for seasonal work.as a landscape gardener in Glasgow, earning multiple awards in both Scotland and Ireland.

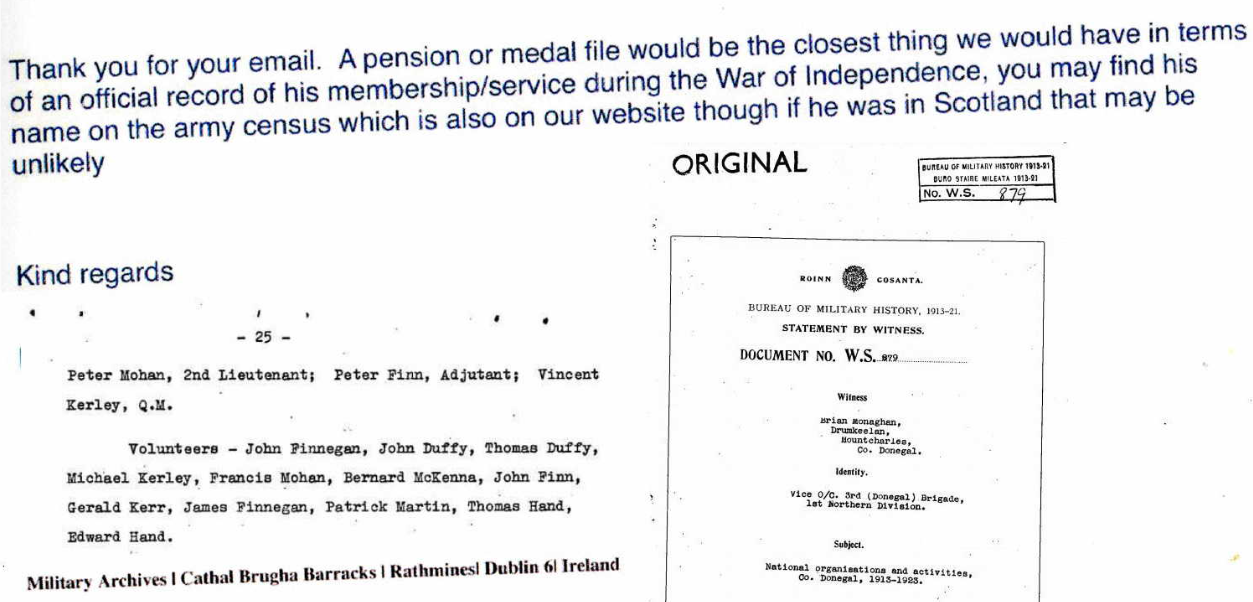

The area where he lived was known for its strong Irish Republican sentiments and was one of the last places to experience full English, and later British, control in Ireland. Records from the Irish Defence Force indicate that Francis received a pension for his service during the War of Independence. Additionally, they suggest he had been a local volunteer in the Irish Republican Army prior to independence.

Francis married Catherine Cunningham from Coatbridge, a Scots-Irish Catholic coal mining family, on December 27, 1907, in Shettleston, an area of Glasgow known for its vibrant Catholic Irish migrant community and IRA affiliations. Catherine’s coal mining brother was a frequent visitor to their secluded gardener’s cottage near Tollcross Park. During this time, Francis often took the ferry to Ireland and even visited New York to see Irish relatives.

Francis lived until he was 78, dying from carbon monoxide poisoning due to an old gas cooker after falling asleep while cooking eggs.

At Francis’s funeral, a quartermaster general of the IRA reportedly attended. Initially dismissed as an embarrassing family story, records from the Irish Defence Force later confirmed that a Francis Moohan was pensioned for his service as an Intelligence Officer for the early Irish state in Tollcross during the 1920s. During this time, towns across Scotland with significant Irish populations collected supplies that were smuggled into Ireland. Eamon de Valera, president of the Irish Republic from 1919 to 1922, stated that financial contributions from Scottish communities surpassed those from any other country, including Ireland. Irish miners secured gelignite from Scottish mines to ferry across the Irish Sea, and fundraising efforts in places like Coatbridge were crucial to the cause.

Given the heavy toll Mary’s father, William Yardley, paid for his heroics in WWI, it’s perhaps unsurprising that she married John Mohan, son of Francis and Catherine, when WWII arrived. She wanted to ensure her children wouldn’t grow up fatherless as she did or with the burdens faced by many “silent generation” families. She also left the Free Church of Scotland to become a Catholic, which must have required tremendous courage.

Life is a tapestry of grey, not merely a stark contrast of black and white. Our experiences shape us as both victims and perpetrators. The unwavering commitment to defend the powerless is the closest definition of ‘good’ versus ‘bad.’ In a complex world, this commitment should remain unchanged, regardless of who leads the charge.

This is our finest tribute of remembrance for those who fought so that we need not. It embodies the true meaning of Remembrance: “It is not for glory nor honour that we fight, but for freedom, which no honest man gives up but with life itself.” Lest we forget.